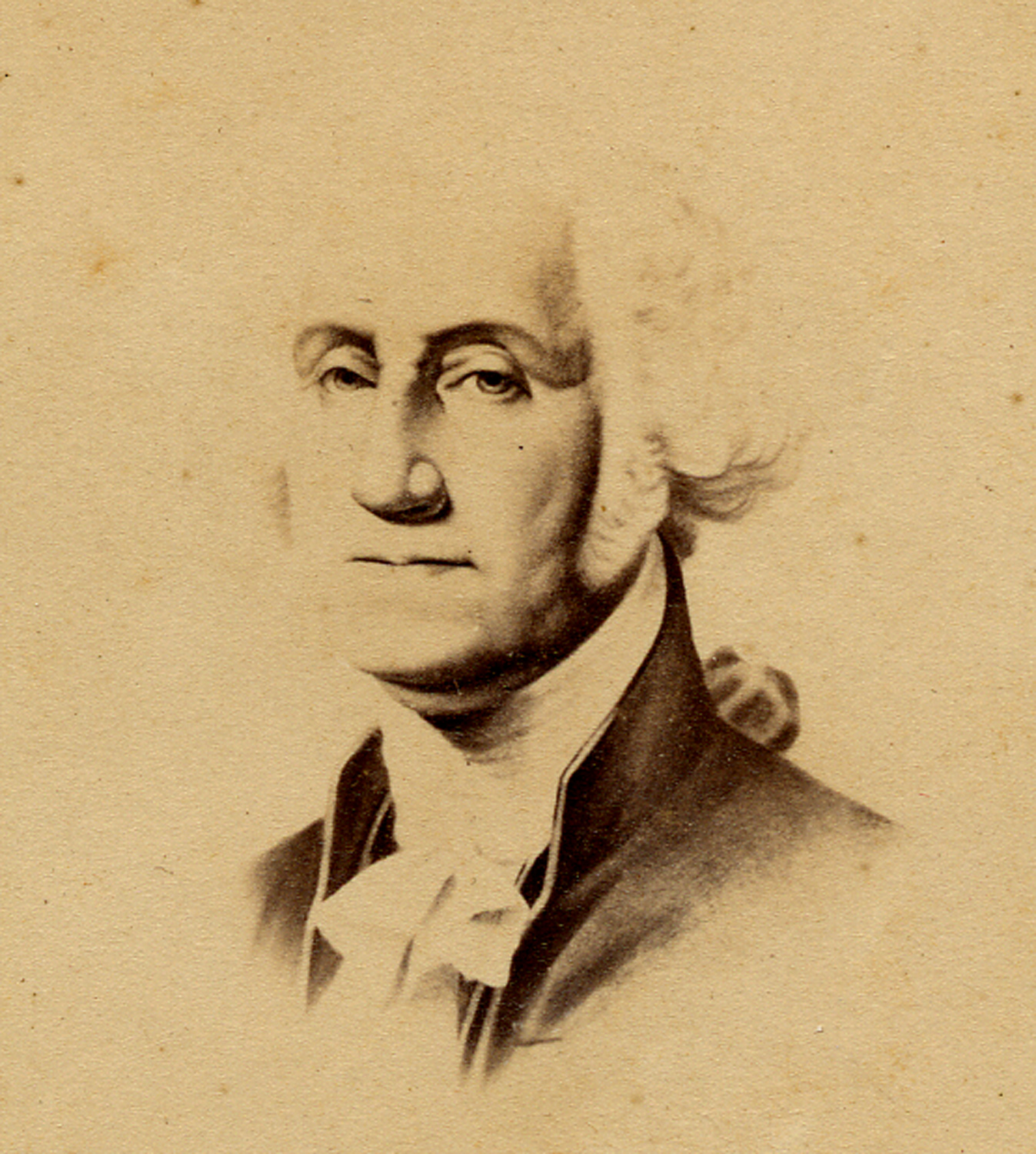

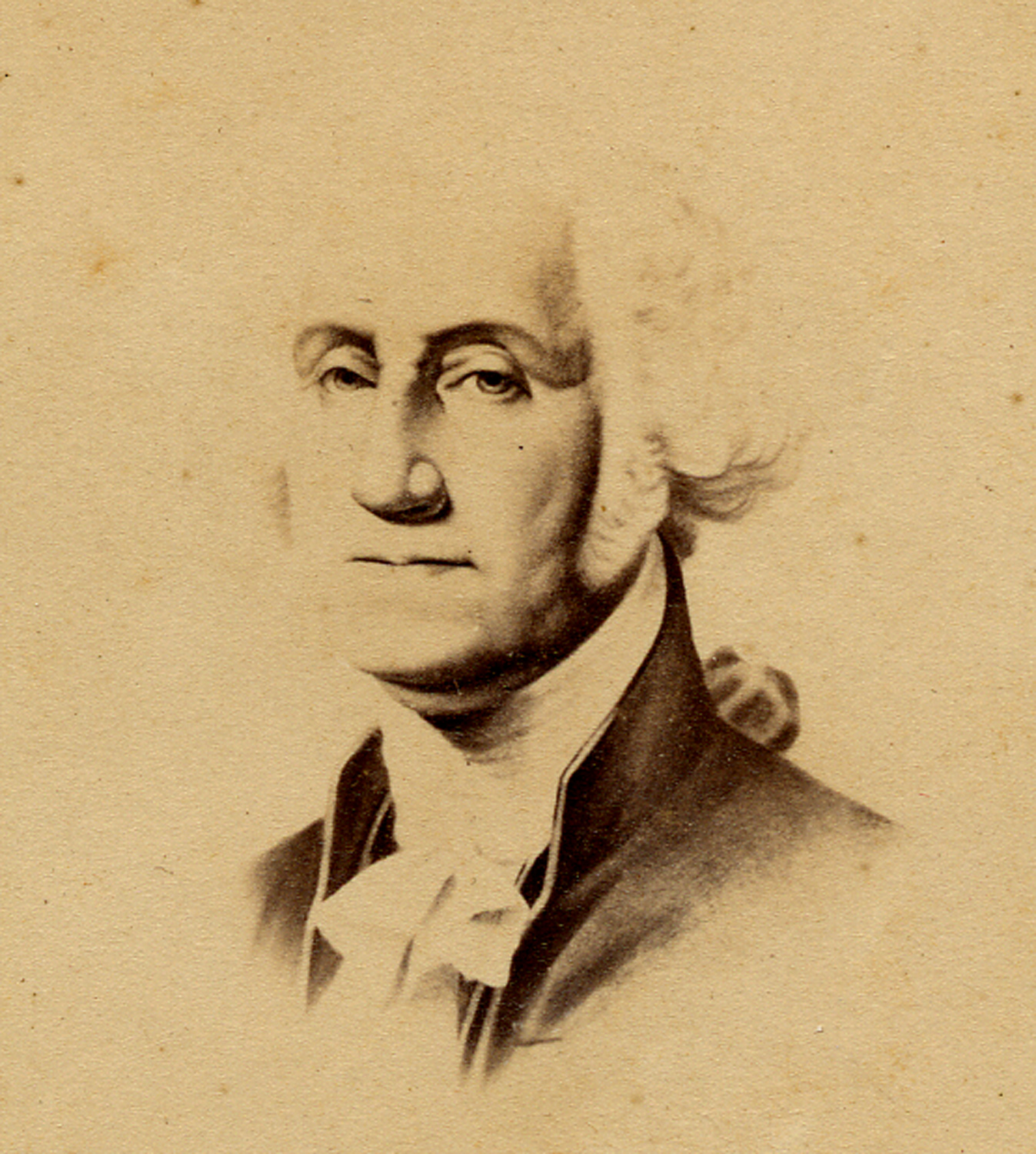

George

Washington

Born

in 1732 into a Virginia planter family, George Washington grew to become an 18th

century Virginia gentleman. He pursued two interests: exploration and the

military. At 16 he helped survey the Shenandoah Valley. In 1754 he was

commissioned a lieutenant colonel and fought in the first skirmishes of the

French and Indian War. As an aide de camp to General Edward Braddock, he

narrowly escaped death as four bullets ripped through his clothing and two

horses were shot from underneath him.

From

1759 to the outbreak of the American Revolution, Washington managed his lands

around his home at Mount Vernon and was elected a delegate to Virginia. He

married Martha Dandridge Custis. But like his fellow Virginia planters,

Washington soon felt exploited by the British.

When

the Second Continental Congress assembled in Philadelphia in May 1775,

Washington was elected Commander in Chief of America’s Continental Army. He

took command of his troops and embarked upon a war that lasted six years.

Finally in 1781, with the aid of French allies, he forced the surrender of

Cornwallis at Yorktown.

Although

Washington desired to retire after the war, he soon realized that the nation was

not functioning well under its current Articles of Confederation, so he rallied

for a Constitutional Convention, which met at Philadelphia in 1787. When the

Constitution was ratified, the Electoral College unanimously elected Washington

president. George Washington took his oath of office as the first President of

the United States on April 30, 1789.

To

his disappointment, two political parties were developing by the end of his

first term. Tired of politics, he retired at the end of his second term. In his

Farewell Address, he urged his countrymen to avoid excessive party spirit and

geographical distinctions and warned against long-term alliances with foreign

countries. Washington enjoyed less than three years of retirement at Mount

Vernon before he died of a throat infection on December 14, 1799.

Following Washington’s death and into

the early 19th century, many local militia units around the country

changed their names from their city or state affiliations, to “Washington,”

in honor of America’s first president. George Washington’s legend was still

strong across America and his birthday was a day of celebration in which local

militia units paraded.

When the first official American

militia was formed in Louisiana following the War of 1812, sometime between 1814

and 1819, one of the artillery units of the preexisting French Battalion of New

Orleans Volunteers changed its name to the Washington Artillery.

Newspaper accounts in 1819 document the

earliest known use of the name “Washington” with one of these artillery

companies. The Louisiana Courrier,

dated January 11, 1819, reported that on the anniversary of the Battle of New

Orleans on January 8th the governor of the state reviewed local

militia companies. Among the military units listed was the Washington Artillery

(foot), Captain B. Williams commanding. Later that year, The Orleans

Gazette and Commercial Advertiser newspaper published a notice dated

November 26, 1819 that “Washington Artillerists … assemble in front of the

Presbyterian Church, in full uniform, at 2 o’clock.”

Research of Louisiana’s 18th

century French and Spanish militia documents an overlapping continuity of

personnel within the artillery organizations with each transfer of governing

authority. As each artillery unit reorganized and renamed itself under various

dominions, its members volunteered their services to protecting their homeland.

These artillery units were the ancestors to the current Washington Artillery.

With this proud early history, it is

quite evident why New Orleans’ Washington Artillery could draw new members

from the city’s social elite year after year, and why, when asked, many

Washington Artillerists would say, “The Washington Artillery wasn’t named

after George Washington. He was named after us!”

HOME